- Gorm, Thyra and Harald

- The rune stones

- Gorm the Old’s rune stone

- Harald Bluetooth’s rune stone

- Basse’s rune stone

- How are rune stones read?

- The rune stones past and present

- Henrik Rantzau’s view, 1591

- Jon Skonvig, 1627

- Søren Abildgaard, 1771

- Ole Jørgen Rawert, 1819

- Adam Müller, 1835

- Jakob Kornerup, 1861

- Julius Magnus-Petersen, 1869-71

- Julius Magnus-Petersen, 1878

- Hans Andersen Kjær, 1897

- Photographs by a member of the public, 1935

- Runologist Erik Moltke, 1971

- Ludvig Stubbe-Teglbjærg’s rubbings, 1973

- Peter Henrichsen, moulding and copying in 1984

- Roberto Fortuna, 2006

- The conservation investigation 2006-08

- 3D light scanning, 2007

- Harald Bluetooth’s rune stone at home and abroad

- Pictures from Jelling

Jon Skonvig, 1627

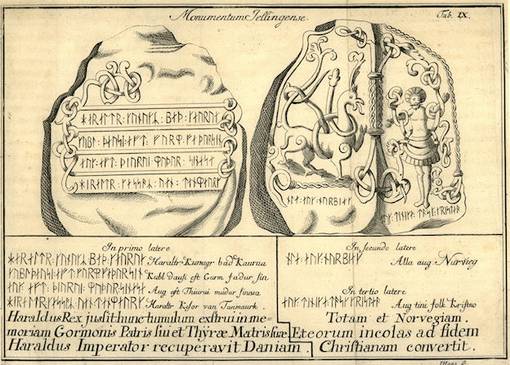

In 1627 the Danish professor and antiquary Ole Warm (1588-1654) sent his illustrator Jon Skonvig (d. 1664) to Jelling to produce illustrations for Worm’s planned book on known rune monuments in Denmark. The work ’Monumenta Danica’ (Danicorum Monumentorum libri sex)’ was published in 1643.

Skonvig drew Gorm’s small rune stone horizontally and he mistakenly showed the two inscriptions adjacent to each other. In Worm’s text it is written about the rune stone “Lying near the church’s door, thus it can provide a seat for the tired”. Worm’s work also features a woodcut, which Christian Friis of Kragerup had sent to Worm in 1639. In this woodcut both stones stand in front of the porch. Therefore Gorm’s rune stone was probably placed in its present position between 1627 and 1639.

Skonvig of course also drew Harald’s large rune stone. In his sketch the stone’s proportions and shape match the reality reasonably well, but Skonvig’s abilities to reproduce the motifs were extremely limited. In addition, there are significant differences between the sketch and the final illustration in the form of a woodcut. Skonvig reduced the quantity of foliage in the woodcut and he also showed Christ standing down on the band of runes.

The Runes

The inscription on Gorm’s small rune stone is reproduced in its entirety in both Jon Skonvig’s sketch and woodcut. This also applies to the words karþi and kubl, where runes are missing today due to breaking off of rock from the surface. In the woodcut of Harald’s large rune stone it can clearly be seen that the stone’s top had already broken off by that time and that around half of the ornamentation on the text side had disappeared. In the sketch Skonvig has drawn a gap in the rune text on the Christ side, whilst he shows four rune symbols in the woodcut. This forms the words tanika tąsk, when tãni karþi should have been shown. This has led to uncertainty about the inscription. The reason for this must be that as early as 1627 the runes were incomplete because of loss of stone from the surface. In addition, Skonvig has filled in the inscription on the text side with wrongly interpreted runes and sequences in areas where decomposition is visible today.

An assessment of the condition of the rune stones in the 17th century based on Skonvig’s drawings is problematic and the documentary value of the drawings can therefore only be on a general level. However, Skonvig was by and large a capable rune reader. He has left us with an important and usable source and made a pioneering contribution to the runological field.