- Gorm, Thyra and Harald

- The rune stones

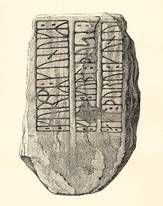

- Gorm the Old’s rune stone

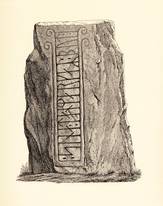

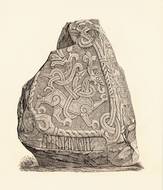

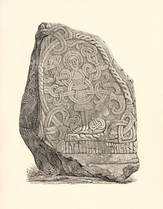

- Harald Bluetooth’s rune stone

- Basse’s rune stone

- How are rune stones read?

- The rune stones past and present

- Henrik Rantzau’s view, 1591

- Jon Skonvig, 1627

- Søren Abildgaard, 1771

- Ole Jørgen Rawert, 1819

- Adam Müller, 1835

- Jakob Kornerup, 1861

- Julius Magnus-Petersen, 1869-71

- Julius Magnus-Petersen, 1878

- Hans Andersen Kjær, 1897

- Photographs by a member of the public, 1935

- Runologist Erik Moltke, 1971

- Ludvig Stubbe-Teglbjærg’s rubbings, 1973

- Peter Henrichsen, moulding and copying in 1984

- Roberto Fortuna, 2006

- The conservation investigation 2006-08

- 3D light scanning, 2007

- Harald Bluetooth’s rune stone at home and abroad

- Pictures from Jelling

Julius Magnus-Petersen, 1878

In 1875 a bad atmosphere had arisen amongst Danish archaeologists, as there were no signs that Professor Peder Goth Thorsen would get his work on the Danish rune stones published. Therefore the society called Det Kongelige Nordiske Oldskriftselskab asked the runologist Ludvig F. A. Wimmer (1839-1920) to begin a new and original work about the Danish rune stones. The society granted a sum for the preliminary work. Julius Magnus-Petersen was again chosen as the illustrator. In his memoirs he wrote afterwards about his collaboration with Wimmer, ”I am both happy and benefitted by the fact that Professor Wimmer was with me everywhere in my work on each stone, as opposed to Professor Thorsen, who did not accompany me on one occasion; I felt that besides daily to be in the company of the fine scholar, his presence in my work too was a guarantee of the accuracy of my drawings”.

The two men were in Jelling on the days July 25-29 1878, but despite Wimmer’s enthusiasm his work on runes was not published until 1895. The small rune stone’s front side was excavated so that it could be drawn in full size and it is noted that ”the influence of the weather has made the runes in all three bands on the front side as well as the border lines and punctuation marks, that in themselves are broad in the deep and clearly carved lines, very unclear in their edges, and they become still more and more diffuse.” Wimmer continues ”In the inscription on the back side the runes are not like on the front side, diffuse at the edges, but have still preserved the original outline very well, which without doubt must be explained by the fact that this side has not been so heavily exposed to the weather’s unfavourable influence as the front side and perhaps also over a long period has been hidden by the ground…” and ”whilst the first two words in the line are clear and sharp [on the back side], the last (buT) and especially the points and the border line subsequently as well as the spirals, which the border lines run into, stand out somewhat more weakly.”

[Translate to English:] Unikt syn af Gorms runesten

In 1878 Magnus-Petersen had the opportunity to draw the whole front side of the small rune stone, including the part which is normally under the ground surface. It appears from the drawing that there was no damage of significance to the condition of the stone. Relevant to this on the other hand is the broken of area in the inscription’s second and third lines. It displays a different extent to that shown in Magnus-Petersen’s own drawing from 1869-71. Then he drew a broken-off piece on the stone’s surface in the bottom right corner, which was apparently not missing in 1878. This obviously does not make sense. The reason for the difference may be explained by Wimmer’s presence. He has looked over Magnus-Petersen’s shoulder and could have dictated an interpretation of the stone’s state of preservation, when it was unclear. This emphasises the fact that drawings should always be looked on as subjective and not objective.

The drawing from 1878 shows further details about the stone’s state of preservation. These include that the line separation is missing in the broken-off area, which it was not in 1869-71. In addition, the broken-off area has extended upwards. The large crack through the second line of the inscription is clearly marked, as is a crack on the side of the stone. In addition, there is a broken-off piece in the first line, which represents a worsening of the condition of the stone compared to the drawing of 1869-71. On the back side the last word but and the last punctuation mark are fainter than the rest of the inscription. Magnus-Petersen has reverted to the traditional interpretation of the rune band’s termination at the top, with two spirals on each side.

On Harald’s large rune stone the large crack over the text runs right down in the upper line of runes and therefore is of the same extent as it is today. In addition, the same damage is visible that was previously shown by Adam Müller (1835), Jakob Kornerup (1861) and Magnus-Petersen himself (1869-71). However, the cracks at the top are not drawn so pronounced as in 1869-71. On the animal side the crack running downwards from the broken-off triangular piece is drawn as it was by Kornerup. The cracks on the side of the stone to the left of the animal are of the same extent as today, whilst the cracks toward the bottom of the stone have more or less the same extent as those shown by the previous illustrators. There are a number of broken-off areas on the upper knot.

On the Christ side Magnus-Petersen has drawn a crack across the band around Christ’s right wrist. In addition, there is a crack to the right near Christ’s left hand. The long crack in the middle of the stone over Christ’s feet is not shown clearly, though it is marked. In 1869-71 Magnus-Petersen drew a clear broken-off piece in the knot toward the animal side, which appears as a more diffuse area of broken-off rock in 1878. The large broken-off piece in the rune band is also imprecise in its demarcation as in the 1869-71 drawing, but it is clear that the broken-off area has increased in extent over the 10 years to include the k rune in kristna.

As well as the drawings Magnus-Petersen painted watercolours of both rune stones. He also made paper impressions of Christ’s face and selected words, including the sequence haraltr. Today the paper impressions are stored in the Royal Library.